Sophie Dahl

When I have seen pictures of my wife, taken by some of the world’s important photographers, I recognise her, but not entirely as the woman I am married to who has borne our two children. I recognize the beauty (though in truth, she is more beautiful in real life), I recognize those enormous eyes (that I often think could successfully land a light aircraft in the fog), and I certainly recognize those long limbs and pale, clear skin. I recognize the charisma and electricity that courses out of those sharp cheekbones. But there is something there I don’t recognise; a certain look, a character that seems to exist outside of this woman I know. I have stood next to a two storey picture of her on the street waiting for a taxi; a full 10 minutes went by till I realised it was her.

Sophie really put the breaks on her modelling career when we met. It no longer felt fully compatible with the life of a writer (and latterly a mother), and though she has since dipped her toes back into those waters, I never really knew her when she was someone flying off to Milan, Paris and New York at a moments notice to shoot a campaign for some illustrious fashion house. This was of course what her life used to be but as she decided to scale it back, it became more sporadic. The working Sophie I got to know was the one hunched over a computer she barely knew how to work, and often broke, in a haze of cigarette smoke, tapping out words, stories and articles late into the night. The one I knew was more often to be seen behind the stove making notes on measurements and cooking times with three or four versions of the same cake in her slipstream. This was the Sophie I fell in love with.

When she did a Vogue cover a year or two into our relationship I would be utterly proud, humbled in fact by her beauty. Staring at me from the cover of the world’s leading fashion magazine, I tried to square that image with the girl I knew who laughs into her tea, who dances to Ol’ Dirty Bastard in her pyjamas, who can read a book faster than the robot from Short Circuit, the girl I proposed to, who magically said yes.

The fashion world that Sophie had occupied for many years had not been an industry I had crossed paths with until now. Suddenly I found myself at the occasional party shaking the hand of Valentino, Tom Ford, Karl Lagerfeld, Frida Gianinni. One of my photographic heroes, Tim Walker, a friend of Sophie’s, came over for lunch. I attended my first runway show, in Paris, and at the after party watched my wife and Daisy Lowe bump and grind to Dizzee Rascal. In nearly all cases, it was more glamorous than I imagined. As we went backstage at the Louis Vuitton show Sophie warned me: “Careful, you're about to see a lot of naked girls, and you absolutely don't want to look like you're looking because everyone will think you're a perve. I already know you're a perve so that's fine."

It was a world that is easy to dismiss if you are not a part of it, the gates of it seeming so high and gilded that it's easier to write it off as something vacuous. And as I peeped behind the gates (as unpervily as I possibly could) the artistry on show was inarguable. The clothes are one thing certainly, but the creation of the pictures was the part that excited me the most.

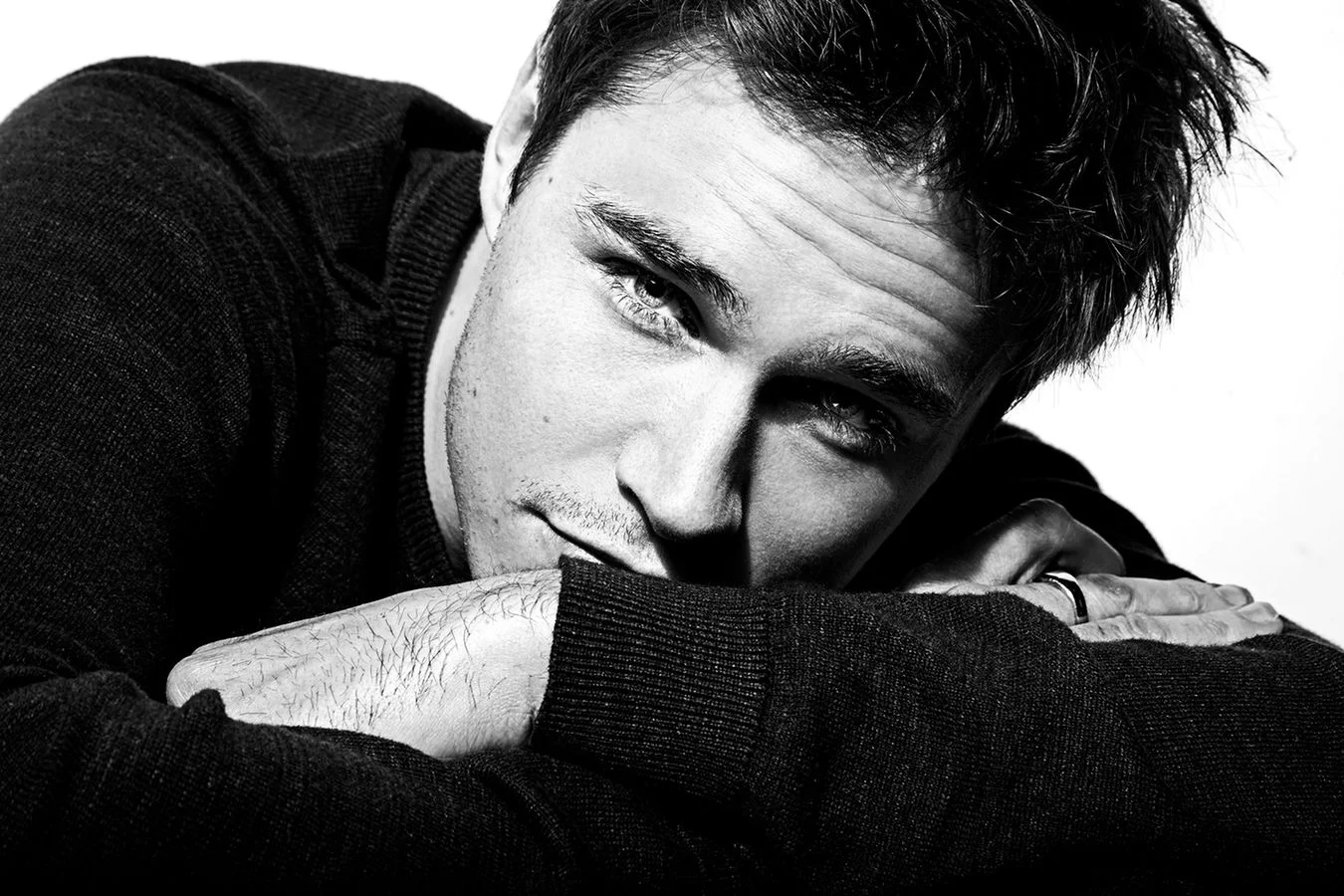

I have had a major interest in photography since my early teens. In fact it was the black and white photography from a certain era that determined much of the course of the rest of my life. Black and white photos of smoky beat poet, jazz club dives, the musical photographs of William Claxton and Francis Woolf, the raw beauty of Cartier Bresson’s Paris. They all lead me to jazz, beat poet literature and of course Paris and New York. They also lead me to my mother’s dust covered Pentax K1000, a weekend course in photography and developing at Chippenham Tech College and eventually film school. When I was studying film, focussing on Japanese and Polish Cinema, I seriously entertained dreams of becoming the next Gordon Willis or Roger Deakins. I didn’t, but I did continue to pursue my love of photography quietly alongside my music career. They seemed conducive to each other as I was always on the road with interesting things to document. Early on in these travels I had my photo taken by Bruce Weber for Vanity Fair. I spent most of the half day shoot badgering him about Chet Baker and his collection of vintage Leicas. We did some shots, but despite his kindness, I was nervous and out of my depth.

I realised quickly as I found myself in front of the camera more and more, that I was far happier behind it, taking light readings, composing shots and checking proof sheets. I am better at it now but it is instructive to point out that the first photo shoot I did for Universal Records in support of my album Twentysomething in 2004 was entirely canned due to the painful, distressed expression on my face throughout the few hundred shots taken.

I have taken thousands of photos of my wife and our family since we have been together. They are like any archive, of any blossoming family and the various stages. The first rush of love, the first house, the first child - they’re all there, spread across various hard drives. A record to our time together in all its unglamorous, yet undeniable, beauty.

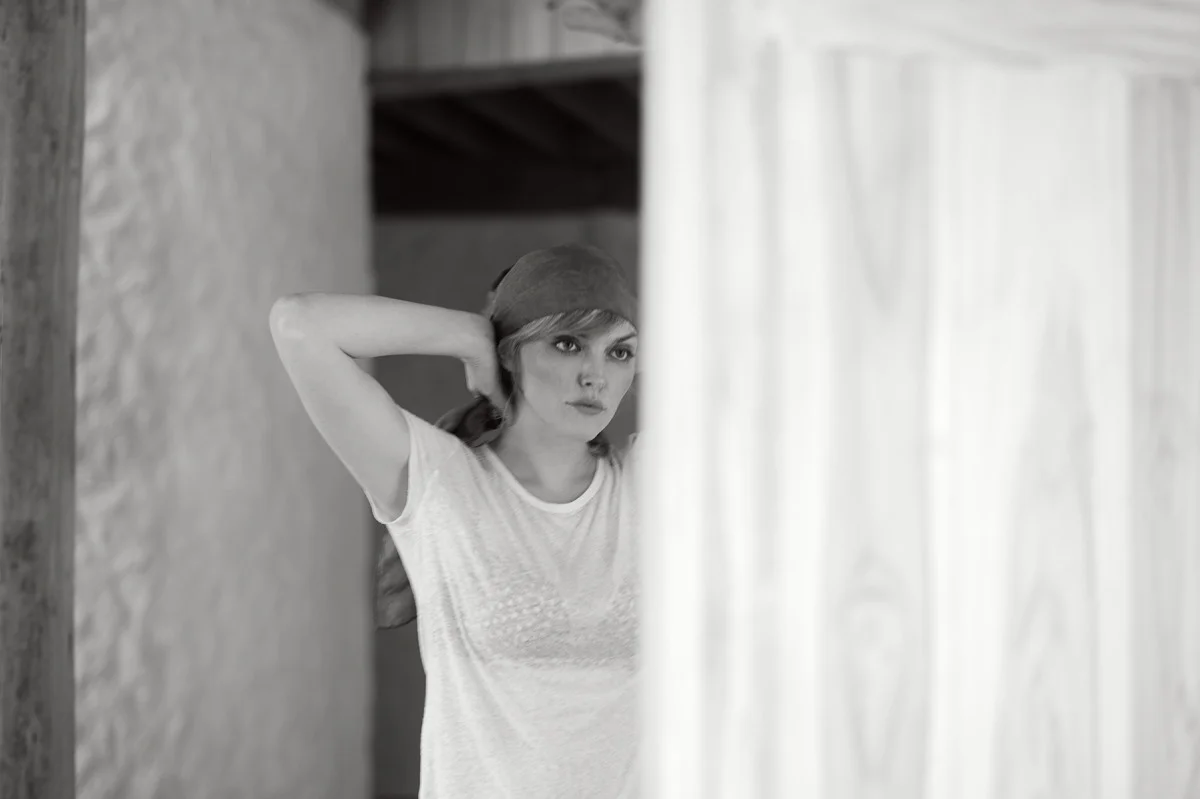

The idea is floated that I take some ‘proper’ photos of Sophie. Just me and her. No hair and makeup, Sophie calling the shots with the styling and positions and me just trying to get the bloody picture right. In the wake of the people to have taken my wife's photo (a roll call of the world’s most important photographers - Richard Avedon, Tim Walker, Steven Meisel, Herb Ritts and Bruce Weber to name but a few) I grab a 50mm 1.2 lens and a Leica Monochrom that only shoots black and white.

So here we are - myself, my woman, a beautiful beach on our recent holiday, some dusky light (Sophie refers to it as ‘the magic hour’ - a pro term no doubt) and damn it, if I don’t start to feel a little nervous. We have shared an amazing but nevertheless intense last three years together, out of our seven. Two girls born exactly two years and two days apart, house moves, scant amount of sleep and two world tours. It is fair to say we know each other pretty well by now. Suddenly though I see this body, this face, my love, in a new way. Through the lens I look and frame her as the light gently accentuates her features, her arms and hands moving into shapes I am unfamiliar with. The camera is manual so I fiddle frantically with the shutter speed, the exposure, and move the focus wheel back and forth. She twists, she turns, her huge eyes sparkle. It’s all, well, I cannot deny, very, very sexy.

A lot of things make sense to me at this moment. As an amateur photographer I realise how important the subject is and how genuinely the camera lens can indeed ‘love’ certain people’s faces. A delicate chin, an elegant nose, cheekbones that can cut glass. There is beauty, but there is also the poetry of shape, symmetry or perhaps the perfect lack of. Creating these moments for the photographer is a skill. The photographer has to capture it but the model has to create it. More importantly though I am reminded of the mysteries of intimacy and how it reveals the layers of a person over time, how it keeps surprising you, just when you think you really know someone. As the shutter clicks and the sun goes down, a whole new side leaps out at you in purest black and white.