Gregory Crewdson

When asked to contribute to this issue of Un-Titled Project devoted to cinema and the cinematic, I was thrilled. Then, I was struck by the irony that all the images reproduced in the magazine are, by necessity, stills.

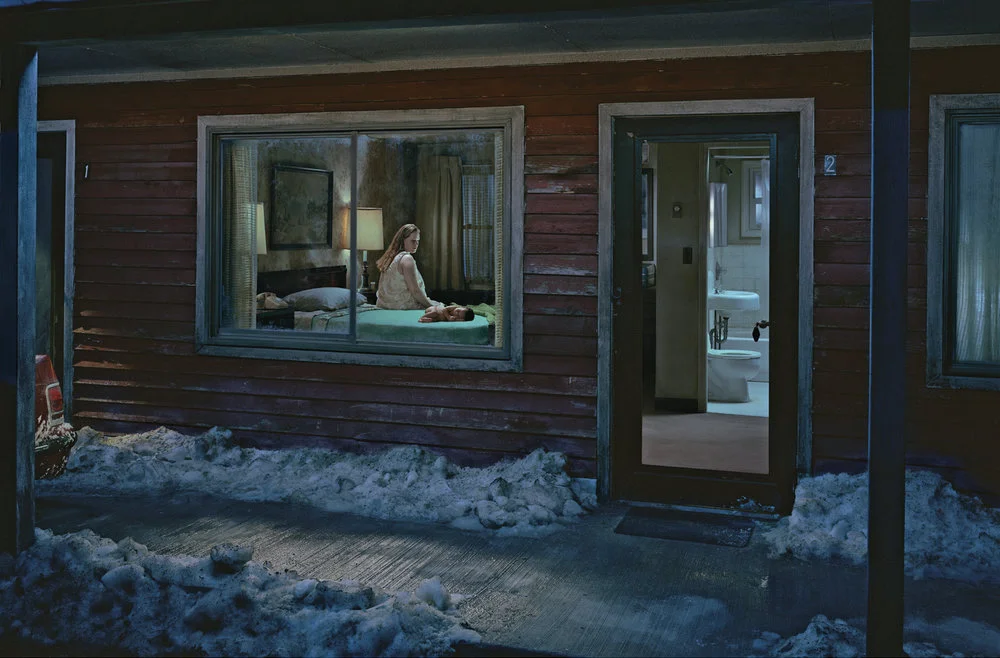

Few artists practice the art of the still and stillness better than Gregory Crewdson. His series of large-scale, highly fictionalized, irreal, and suspenseful pictures often depict desolate and dystopian landscapes, and urban or suburban exteriors and interiors that are peopled by characters on the verge of something not quite right. When I first encountered Crewdson’s work, I was struck by how much he imbues psychological texture in stillness. He introduces the viewer to unresolved narratives. He employs a repertoire of cinematic cues that tip the viewer to recall suspenseful cinematic memories.

His pictures are still that are cinematic in effect and in design. Each series is a major production involving crews, location scouting, and casting. The productions Crewdson intends to fashion into stills differ from others whose goal is to create movement for the big or small screen. Crewdson experiments with how we experience, interpret and quote cinematic style. His cinematic signature preserves in an inert form the performative. In his work, I sense a deceptive emotional quietude.

A cinematic trope: picture it. The weekend before the Fourth of July I am at Third Streaming Gallery. Crewdson is in Massachusetts for the holidays. He prefers to give interviews by phone. I call him at our scheduled time from the gallery landline. I have my questions neatly typed in one hand; my Blackberry, whose recording function I tested the previous week, is in my other. The artist answers. I put him on speaker. I push record on my phone. Crewdson has an eloquent and mellifluous voice and measured tone that calms me and eases me. We joke a little about the danger of losing an audio file or film footage. We discuss his extensive body of work for about an hour. I begin to take notes but realize that’s a waste of time because my handwriting is unreliable. I go into serious art critic mode. I want to talk about how his photography can be interpreted to examine rural versus urban or suburban. My interest in post-Fordism leads me to question him about any connection to the isolation and depopulation I see in his work with current critical issues such as migration of peoples and the decline or reinvigoration or public space in America during the last 30 years. I try to get him to acknowledge that his New York suburban upbringing contributes to cinematic and mythic Americana.

His Sanctuary series, starling images of the depopulated and decaying studios at Cinecittà, came about because of his vital interest in cinema. I try to pooh-pooh this obvious retelling by suggesting that these pictures are in fact a much better documentation of urban blight than much of “decay porn” photography of my hometown Detroit. He deflects most of these attempts to fix his work in any specific cultural context. I understand that Crewdson prefers that his images speak for themselves. Nonetheless, he doesn’t shy away from my questions about land use or the blue/red state divide—I think he finds this inquiry interesting. Yet, he brings me back to his love of cinema. Suspense and the unknown are often mentioned as seminal themes in his work so I mention that Marnie and Vertigo are my favorite films. He likes this because he acknowledges that Hitchcock is an unmistakable influence in his work. I know it because he and other writers have mentioned this in other interviews that are contained in the 100 page press package that Gagosian Gallery has provided me. Then I talk about fashion photography because I want to find a different way to discuss high and low forms of visual culture. He tells me that he is often asked to shoot for magazines and is very interested. But his production schedule intervenes. That is my last question. I express my gratitude and tell him how much I enjoyed our talk. He returns the compliment. I hang up. I have a shot of cachaça. In August, I am in bed at home to transcribe the interview. I find the audio file on my phone and press play. I type two sentences and stop because Crewdson has stopped speaking. I press play again and wait to start where I left off in my transcription. Crewdson stops speaking at the same moment as before. I react in horror that I recorded about a minute and a half of our hour long conversation. I imagine that my expression was very similar to the still, drawn faces in Crewdson’s work. I also reflect on Marnie when she spills red ink on her prim silk blouse.

All images © Gregory Crewdson. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery