Dustin Lance Black

Dustin Lance Black is a troublemaker. From his passionate, yet controversial, acceptance speech at the Oscars in 2008, to playing a major role in defeating Prop 8 (a statewide ballot that would have made same-sex marriage illegal in California), the award-winning screenwriter, director, and social activist is not afraid to stand up for what he believes. A powerhouse of art and activism, the 41-year-old Black took some time to share his thoughts with us on the Supreme Court’s recent ruling on Marriage Equality, gays in Hollywood, coming out to his Mormon mom, and what area he trumps his partner, Olympic diver Tom Daley in.

Thom: First of all, congratulations on the recent marriage equality ruling. What was your reaction when you heard the news?

Dustin: I was in San Francisco, and it was early in the morning because things were obviously unfolding on the East Coast, but to be honest, I wasn’t totally surprised. If you’ve been involved in the marriage equality fight, and its path to the Supreme Court, you saw the writing on the wall. It wasn’t until later that it started to sink in. I went out onto Castro Street, and saw hundreds, if not thousands, of people converging to celebrate. I just remember closing my eyes and thinking about how a kid like me, growing up in Texas, could now fall in love, and think about one day marrying their partner, and knowing that it would be recognized and protected by this country.

I read somewhere that you only allowed yourself sixty seconds or so to celebrate all the small victories leading up to equality. Did you allow yourself more than a minute on that day?

(laughs) Well, I’m not really great at celebration. It’s just not my forte! I really like doing the work. In fact, I liked the work on marriage equality so much I literally put it before my filmmaking. For almost five years it took priority. I’d be working on a script, and if I got a phone call to do a speech in Texas or Michigan, or wherever, I would get on a plane and go. The work is what drove me, though it’s not like I just had a sole focus on marriage equality. In the fall of 2008, Cleve Jones, one of Harvey Milk’s political protégées, and I, published an op-ed in The San Francisco Chronicle saying that the time is now for full equality, not just marriage equality. That’s still the goal. Marriage equality was a huge leap forward, and has brought us much closer to achieving that goal; however, I hope we don’t lose sight of the fact that you can still be legally fired in most states just for being married. So, in no way did I feel that we had fully achieved the goals Cleve and I laid out in 2008. That’s why I didn’t celebrate that long. I took a day, and it was really nice, but by the following day there was an emptiness that needed to be filled.

A few years ago you were part of a group of people instrumental in overturning Proposition 8 in California. Was this your first foray into activism?

I had been involved in the gay rights movement, but never in a leadership capacity. I had done some volunteering at the Gay and Lesbian Center in Los Angeles, and that, combined with the research I had to do writing the movie Milk really opened my eyes. It became clear that we had lost some of the successful strategies of people like Harvey Milk - like building coalitions with racial minorities, with women, with the labor movement . . . the kind of work that needs to be done if your going to win at the ballot box. It seemed to have stopped. It was examining these strategies and seeing that it might be time to revise them that really sparked my desire to take a leadership position in the movement.

“Coming out to my mom was very frightening. My mom loved everybody, but she grew up in the South, she was military, and had been Mormon, so she didn’t think being gay was right.”

Out of this you created the play 8. What inspired you to do the play?

Well, at that point, the case had gone in front of a judge in California, and it was the first time defendants and plaintiffs had to go into court and raise their right hands and promise to tell the truth, and nothing but the truth, about gay and lesbian families. All these myths and stereotypes that had hindered equality for so long would go on trial. I was excited about that because my philosophy was that truth was on our side. If we could just have it be heard, we could change hearts and minds. Well, the opposition also understood that, and so they made sure that cameras were banned from the courtroom, even though the judge was in favor (of them being there). What happened in that courtroom was revelatory; the arguments from those opposing marriage equality fell apart; in fact, their key witness turned on the stand under questioning. It was incredibly dramatic, but no one saw it. There was not even an audio feed. So the play really came out of wanting to let it be known what happened in that courtroom. I could’ve written a movie, but movies take years to make their way to the screen, but I knew I could write a play within a few months, and let the public know what really happened in that courtroom. We did a production in New York and Los Angeles which had a big glittery cast that helped raise much-needed funds to support the case.

During your Oscar speech, you made a bold promise to the young people of America that full federal equality was coming soon. You’ve been open about the fact that you received backlash from certain members within the LGBT movement for making such a promise. Can you explain what their objections were?

Well, the main objection I heard was that there was a thirty-year plan in place, and I needed to get in line and follow it.

Thirty years?

Yeah, thirty years… and it was very specific. It was an incremental plan with a wait-and-see philosophy regarding the Supreme Court; meaning they did not believe we had Justice Kennedy on our side, and that we would lose if we took anything to the Supreme Court. Now, I didn’t have that kind of patience! I guess I had a little more faith in this country, and the law, than they did. If you really looked at the decisions that Justice Kennedy had made prior, it became clear that this was someone who saw gay and lesbian people as equal citizens, worthy of protection. However, the arguments we were hearing from the LGBT leadership at the time was that America is not with us yet, that we don’t have a majority of support. So, I said okay, that’s what we have to change then. We knew we needed to change hearts and minds. I think it was a lack of vision on the part of the LGBT leadership, and perhaps some fear, that we really didn’t deserve it. I’ll tell you though, our case, our plaintiffs, our lawyers...we just didn’t feel that. We knew that we deserved it, and felt we deserved it within our lifetimes. Not thirty, forty, or fifty years from now.

So I have to ask… after the marriage equality ruling, did any of them come to you with their tail between their legs?

No, but they didn’t need to. I think the people who disagreed eventually saw the wisdom of what we were doing. I think very often in the gay community, and even the minority community, there’s interlacing warfare going on. It’s worth remembering that the real enemies are not the people in the movement, even those who might disagree with you. One of the guys I fought with the most was Evan Wolfson who absolutely disagreed with our philosophy. He lectured me pretty brutally for just mentioning the word “federal” in the Oscar speech. But even then, I threw him a fundraiser in my own home because his organization, Freedom to Marry, was also trying to do the good work of moving hearts and minds. Ultimately, we’re all in it together.

What’s the next big issue within the movement?

The next goal is to pass a federal civil rights act that mirrors the 1964 civil rights act, but includes LGBT people, which would mean that we would have protection when it comes to housing and to jobs. If people felt protected, and knew they couldn’t be fired or kicked out of their homes for being gay or lesbian, they might actually start to come out and share their lives with their co-workers and their communities. In order to have that, we need to have security, and that’s going to take a federal civil rights act. I’m afraid that if we just went state by state, city by city, it could take a century.

Given your activism and eloquence on these issues, it’s easy to assume you’ve always been comfortable in your own skin. In my research, I saw that you had a lot of cards stacked against you growing up. I’m wondering if you could share some of your personal story, and the power of coming out. I know it’s a long story, but…

Well, there’s a book in there somewhere, but I won’t give you that much! My challenges started with being born into a very conservative Mormon family. If you grew up in a Mormon church you heard the prophet, Spencer W. Kimble, equate being gay with being a murderer. That’s a hard thing to hear when you’re six years old, and already have a sense that you’re a little different then your friends and your brother. Then add growing up in the South to that, and also being a military family. My mom worked civil service in the Army, and I had a step-dad who was in the Air Force. This was all taking place in the period when gay and lesbian people were being kicked out of the military for who they were. It seemed the best we could do as a country at the time was to say, don’t ask, don’t tell, which is such a slap in the face to gay and lesbian people, because the most crippling thing you can do is tell a gay person to hide themselves in shame. So, you know, it was a frightening time for me.

I’d be lying if I said I never contemplated the sort of dire solutions that a lot of kids turn to who are in those circumstances. Gay and lesbian kids are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their straight brothers and sisters, and nine times more if they come from an unaccepting environment. When you tell a young person they will never be able to love, well, what do you have left? But my turn of luck came when my step-dad was transferred out of Texas to the Bay Area in California. He was a Catholic who only went to church at Christmas and Easter, and so the religious tenor in the home started to relax a bit; and because I was so incredibly shy, my mom put me into theater classes. All of a sudden I found my people.

It wasn’t until college when you officially came out, correct?

That’s right. I went to UCLA’s film school and I made a best friend who it turns out was gay, even though we were both closeted and never talked about it. He finally came out and said he’d heard about this place called West Hollywood, which is the gay area, and well . . . it didn’t take long before I said that I’d like to go there. When I did, it was truly life changing because I saw hundreds of openly gay people, and they didn’t have horns coming out of their heads like the Mormon prophet had promised. They didn’t seem depressed like I had heard gay people had to be. They were having a damn good time; and so, you know, at that point my life was changed forever.

“If you’re a public figure who is working actively to hinder the lives of LGBT people, and we find out that they themselves are gay and lesbian, then I’m going to out them.”

And your mom, she finally came around?

Yeah, she did. Coming out to my mom was very frightening. My mom loved everybody, but she grew up in the South, she was military, and had been Mormon, so she didn’t think being gay was right. I think she thought that if you were gay or lesbian your life must be pretty miserable. So, you know, coming out to her was tough. It happened over a conversation around “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Her feeling was that it was too inclusive because gay people could keep it a secret, and still stay in the military. She didn’t feel that was right. Even after I came out to her, it wasn’t like she went around and told the whole family like it was good news. She kept it a secret. It was really hard for her. It wasn’t until she started meeting my gay friends and hearing their stories that she started to realize these people didn’t match up to the stories she’d been told her whole life. She felt that she had been lied to for generations. I often tell the story about how she came to visit right around my college graduation and met many of my friends, and how her position on LGBT equality changed almost overnight, how within a decade she went from someone who thought “don’t ask don’t tell” was too inclusive to showing up to the Oscars wearing a marriage equality ribbon.

It really shows the power of the personal story that you’re such an advocate of.

Absolutely. It wasn’t about arguing politics; it was the personal stories, meeting actual gay and lesbian people that had the power to change hearts and minds. Watching my mom change gave me the confidence to move forward in the face of people like Evan Wolfson. I think if we encourage thousands and thousands of gay and lesbian people across the country to tell their personal stories, we will see the numbers against us change, because truth is on our side.

What are your thoughts on outing public figures?

Well, it’s pretty simple for me. If you’re a public figure who is working actively to hinder the lives of LGBT people, and we find out that they themselves are gay and lesbian, then I’m going to out them. It might be controversial to some, but if you’re working against a community that you’re secretly a member of, then I’m going to let that be known. I’m going to expose their hypocrisy.

What about closeted actors?

Well, that was a real issue ten to twenty years ago when actors would pretend to have girlfriends or boyfriends. I have to say, in my experience, that’s stopped now. The most closeted thing I’ve witnessed now are these young men and women who seem to be perpetual bachelors or single. But the strategy of having a beard has gone by the wayside. Part of that is this generation of actors coming through Hollywood now all have had Facebook and Twitter for most of their adolescence and have come out already. They’ve posted their rainbow flags, or pictures of themselves with their boyfriends or girlfriends at some point. These days, there’s no putting someone back in the closet. Managers and agents just can’t do it anymore, and when they try, they fail.

“I have not seen hesitation at all from studios or networks when it comes to casting openly gay actors and actresses; none, never once.”

I’ve heard agents and managers will sometimes weed out somebody they suspect of being gay.

That is true. My experience is that they’ve all been managers or agents who are older gay men, who are still operating from an outdated philosophy that gay and lesbian people can’t be open about who they are and still work in this business. I think they need to catch up. America is fine with it as long as they’re good actors.

With Hollywood so dependent on the global market now, and having to show films in countries with strict anti-gay laws, do you think we’ll ever see an openly gay A-list actor carry a film?

I believe so. First of all there are so many ambitious and talented gay and lesbian actors out there who would like to be the one that gets a picture green-lit, I feel like it’s just bound to happen. I think that day is coming in Hollywood. Personally, I have not seen hesitation at all from studios or networks when it comes to casting openly gay actors and actresses; none, never once. And I bring it up all the time.

It feels like television is much more inclusive than film in telling the LGBT story.

Television, to me, is always what’s pushed the envelope when it comes to social issues. What’s really heartening to see is how television has moved so rapidly to include trans people, and trans lives into the conversation; because as much as I talk about gay and lesbian people and our needs, there’s no population that’s been subjected to more discrimination and violence than the trans community. It’s really heartening to see how quickly that conversation has moved.

Speaking of television, you’re working on something for ABC.

I am. It’s called When We Rise. It’s an eight hour mini-series on the LGBT movement that follows three very diverse characters from different civil rights movements: the women’s movement, the black civil rights movement, and the peace movement, and how these characters come together to form the fast moving LGBT movement. It follows them and the people they pick up along the way from 1971 to today.

How did it land at ABC?

I wanted to do it with ABC. ABC was my first choice, and that partly goes back to my roots. If you’re a Southern military Christian, you’re probably watching ABC. It’s what I grew up with!

In 2008 you won an Oscar for your screenplay Milk. When did you first hear the story of Harvey Milk?

When I was in high school I would travel up to the Bay Area in San Francisco, and audition at the American Conservatory Theater. It was during that time that I heard bits and pieces of his story. But really, it wasn’t until college that I got the whole story. UCLA had a copy of The Times of Harvey Milk. After I watched that documentary, I just read anything I could about him. I found his story so moving, so vital, and by the way, lost. No one knew who he was! It was so frustrating!

Really?

You have to understand, the people who had been fighting alongside Harvey Milk were dying, and so right there we were losing an entire generation. We were losing Milk’s philosophy. The struggle had changed. People were trying to survive. We’re talking late eighties, early nineties, at the height of the epidemic. People weren’t talking about moving our civil rights act along, they were talking about access to drugs, and dying with dignity. It was not a time people were talking about Harvey Milk. As a film student, I had heard that Randy Shilts’ book (The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk) had been optioned by Warner Bros., and I was really excited about seeing it. But, it never happened. So a decade later, I’m working in the business, and it still hasn’t happened. At that point, I figured this could be a Dustin Lance Black production. I had a good job on Big Love, and I had a credit card, and I thought, “well… let’s see how far we can get with this.”

How long did it take to write?

It took a number of years, partly because I didn’t have the source material. Warner Bros. still owned the book. More importantly, though, I really wanted to meet the real people who were left. I wanted to hear their stories first hand. I wanted to draw my own conclusions. That took a lot of traveling on the weekends to San Francisco trying to track down people like Cleve Jones, who I was told was still around.

How did you finally connect with Cleve?

A friend of mine called and asked if I wanted to write the lyrics to a rock opera he wanted to do on the AIDS Memorial Quilt. He said that the founder of the AIDS quilt, Cleve Jones, was alive, and living in Palm Springs. I thought, “Wait a second, is this the same Cleve Jones that was Harvey Milk’s intern?” It was, and so I went to his house with my friend, supposedly to talk to about the AIDS quilt, but as soon as my friend would go to the restroom, or whatever, I would say to Cleve, “tell me about Harvey Milk,” and his face would just light up. Within a week, I think I said, “I love your quilt, and it’s a national treasure, but let’s do the Harvey Milk movie,” and he said sure. He really helped me go into the portal of the surviving members of the Milk family, and then from there it was just years of research and drafts.

Are you still planning to direct The Statistical Probability of Falling in Love At First Sight?

Yeah, it’s still happening. A number of weeks ago I turned my focus back to filmmaking full time, and now it’s just a matter of getting all these things going again, and deciding if I do it before or after the mini-series with ABC. Probably wise to do it after, so they both get their fair amount of attention.

Speaking of love, you’ve been with your partner, Tom Daley, for how long now?

About two and half years.

You once said, “people are better when they’re in love.” How has Tom made you better?

In my opinion, I believe love makes you better. I think most people understand that you grow in a different way when you’re in a relationship. In Tom I found a partner who I can dream with, and who knows how to make those dreams into a reality.

Which of you is the better swimmer?

I was a competitive swimmer. I went to the state championships representing North Salinas High School in backstroke, and freestyle sprinting. So, I’m actually a better swimmer; he’s a diver.

Are you a Pisces?

Gemini. We both are.

Oh, boy.

Yeah, get Tom and me in a room, and you’ve got four people to interview!

On Twitter you describe yourself as a filmmaker, social activist, and troublemaker. What’s the last bit of trouble you got yourself into? And I want the dirt.

Oh, god.

Just kidding.

When I say troublemaker, I don’t mean, like, I’m out getting arrested for doing something I ought not to be. It really came from Julian Bond, who we lost recently. Julian Bond was the great leader in the black civil rights movement. I had lunch with him one day right before filing a case against Prop 8, and I mentioned how we were receiving a bevy of criticism from the leaders of the gay movement, urging us not to file. I’ll never forget Julian leaning in and saying, “Lance, good things do not come to those who wait, they come to those who agitate.” And I carried that with me from that day forward. I was no longer afraid to cause trouble, to agitate when necessary. I realized it’s often necessary to cause trouble even amongst the people who are your allies. I aspire to be a troublemaker now, even though it certainly wasn’t how I was raised. The Mormon Church didn’t encourage that sort of thing, but now I wear the badge of troublemaker and agitator with honor.

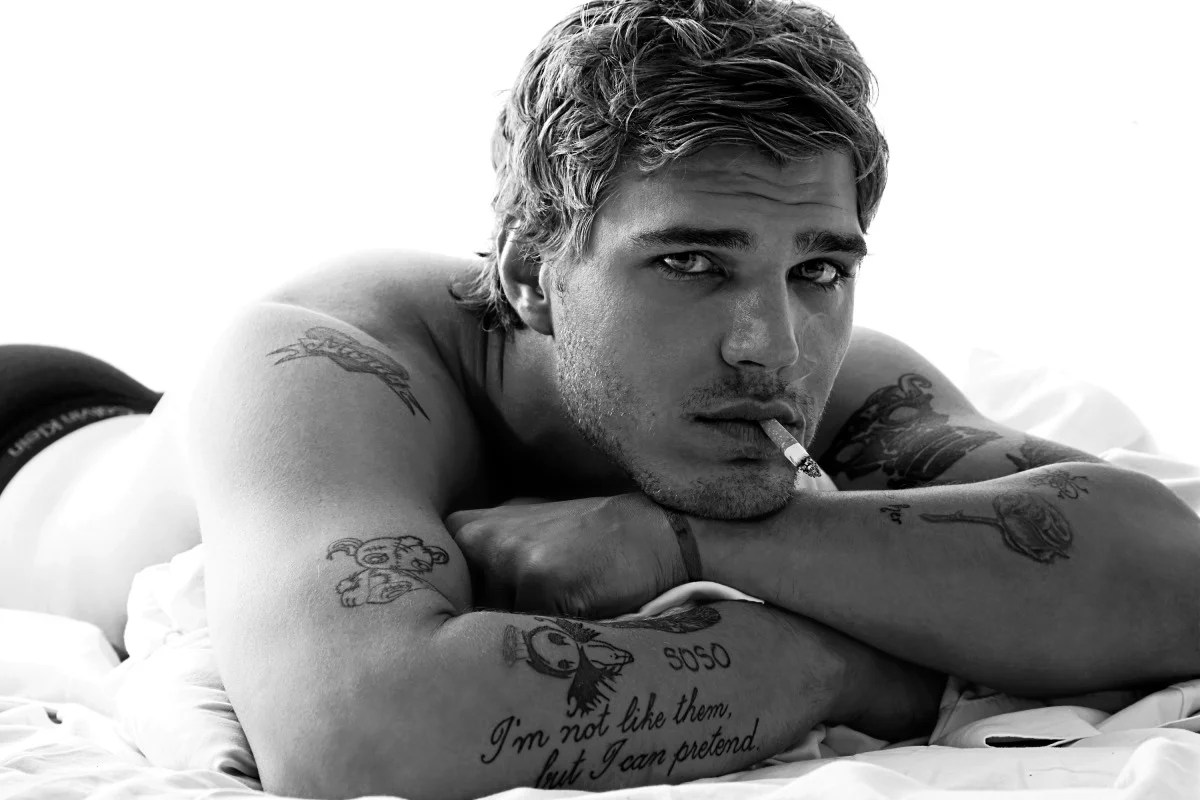

Photography: Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Styling: Sara Alviti

Groomer: Veronica Nunez / Art Department

Producers: Chelsea Maloney & Matt Brown